Already ‘Congruence Engine’ feels like it’s a real thing that might exist out there somewhere, a machine for auto-wrangling similarity. Perhaps, you might think, there’s one tucked away in the Science Museum store somewhere. But, of course, ‘Congruence Engine’ is a metaphor and, like many metaphors, there’s a lot of fun to be had working out what it might mean. But it is also crucial to state at the outset what it is not intended to connote.

So let me be perfectly clear: we are not building a congruence engine, we, the project participants, are the congruence engine. Ours is a human research enterprise where the interlinking ‘cogs’ are the participants and researchers doing mini-investigations, and the totality of what we research creates the congruence we aim for.

Congruence and Difference

Congruence, according to the Oxford Dictionary is ‘the fact or condition of according or agreeing; accordance, correspondence, harmony’. Time and again in the project we will bring together digital records for collections items on the grounds that, in the eyes of participants in the project, they belong together – that they are congruent – even though they have been separated by being held in different collections. The judgement about which items belong together will not be derived from abstract universal categories but will respond to the practical usefulness of bringing items of many kinds together for our particular historical and curatorial investigations of the industrial past.

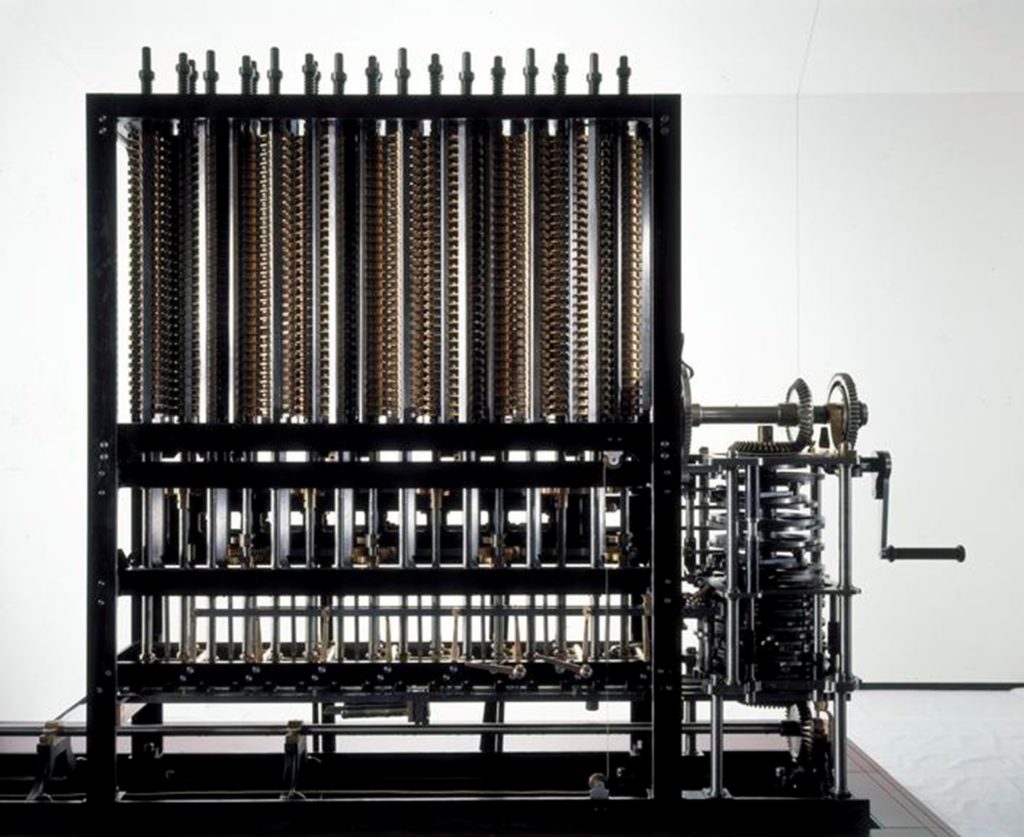

‘Congruence Engine’ metaphorically references Charles Babbage’s difference engine 2, as can be seen here (in the version built in 1991, following Babbage’s detailed engineering drawings from the 1840s for this machine unrealised in its own day).

But Babbage’s engine, designed to reliably produce printed tables for application across commerce, is a million miles away from what we plan in our project. By inventing it, Babbage had hoped to overcome the human error that inevitably crept into tables produced by humans. Closer to our project may be the metaphorical affordance of William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s cyberpunk novel the Difference Engine. This imagines a world in which the information revolution has dawned a century early, driven by the counterfactual success of Babbage’s devices all powered by steam. Similarly, our project imagines a world in which digital tools have been pressed into service to link collections together, with the aim of exploring what is as yet an unknown world of historical and curatorial possibilities.

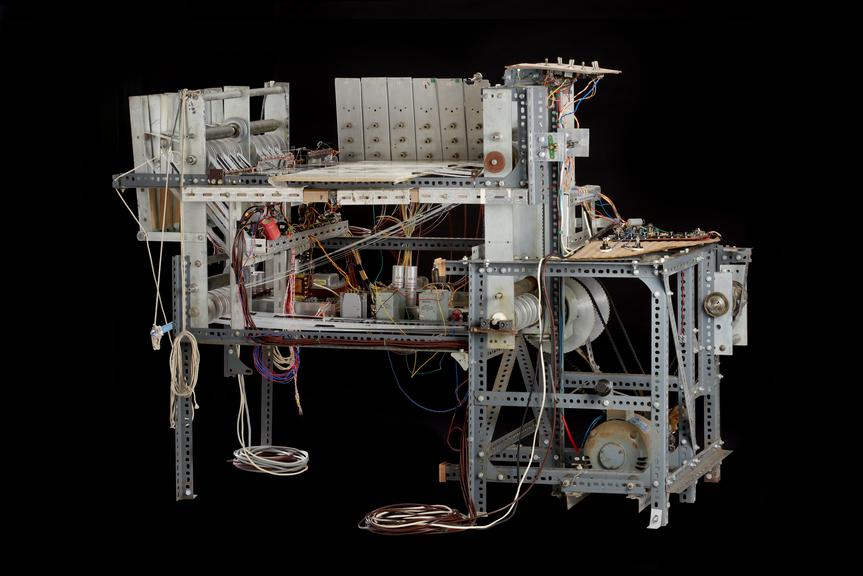

If ‘Congruence Engine’ is metaphorically a machine, it is not one that gets rid of the quirks of individual, but rather one that foregrounds peoples’ specific interests, and is adjusted as it runs to respond to those interests as they develop. In that sense, it is more like the Oramics Machine, a device that its inventor, Daphne Oram, constantly modified as her sonic imagination about what it could do developed. And she always stressed that her machine should be expressive, not ‘turning out music by the yard’. Our Congruence Engine will similarly be adjusted and rebuilt to make it responsive to the participants’ interests and passions. In this way, we plan to model a future world of joined-up collections where the tools do what the users want, rather than the other way round, as can often be the case.

A Prototype Digital Toolbox

If we are not building an ‘engine’, we are certainly working with different programs and techniques to explore how each of them can help support historical and curatorial research. Indeed, we promise in our funding application that ‘the Congruence Engine will create the prototype of a digital toolbox for everyone fascinated by the past to connect an unprecedented range of items from the nation’s collection to tell the stories about our industrial past that they want to tell’. That is clearly another metaphor; one that allows for a variety of approaches to our work. So, the ‘toolbox’ metaphor is appropriate: such a box might contain tools with many uses that are used frequently: a hammer for one job, a screwdriver for another and a wrench for a third. But it might also contain quite elaborate tools that do rather specific jobs rather effectively, but which are used but rarely, like so many power tools. So too it will be with The Congruence Engine project, as we discover, develop and use the different digital tools that will support the investigation.

Hand-Crafted versus Automated

During our previous Heritage Connector project I was struck by another metaphor used by technical colleagues when speaking about digital techniques that don’t use big data and AI techniques; they talked about small scale links between items as being ‘hand-stitched’. It is true that that most historical and curatorial labour is done at this hand-crafted level. To research and write their accounts, most historians consult many archives and read a diversity of literature as they reconstruct the past and analyse its characteristics. Curators too, will at the small scale draw information from a great diversity of sources, perhaps about the objects, images and audio-visual media to include in a display. But the new generation of historical projects that use digital humanities and big data, such as the Turing Institute’s Living with Machines project, employ differing language; there is talk here of ‘data mining,’ and its champions talk of employing AI techniques as being like employing 100 dutiful researchers to do the simple, repetitive, time-consuming work that can make research slow and laborious. The historian Daniel Wilson has suggested that such techniques should be seen as the late arrival of automation into humanities research. But we should also remember that computer-based history has been practised by some historians since computers became available, for example in the work of the Annales School in France.

In Congruence Engine, we will be working along this axis between the hand-stitched and the automated. Specifically, we will be looking at the potential for automating the kinds of data gathering from many sources that has conventionally been done laboriously by individual researchers. We will be asking how well automated digital techniques can achieve what otherwise requires many kinds of ‘inside knowledge’ and developed intuitions about how to conduct research. And we will be monitoring how this changes the kinds of accounts of the past that are possible for participants to construct.

Who are the ‘We’ in ‘We Are Congruence Engine’?

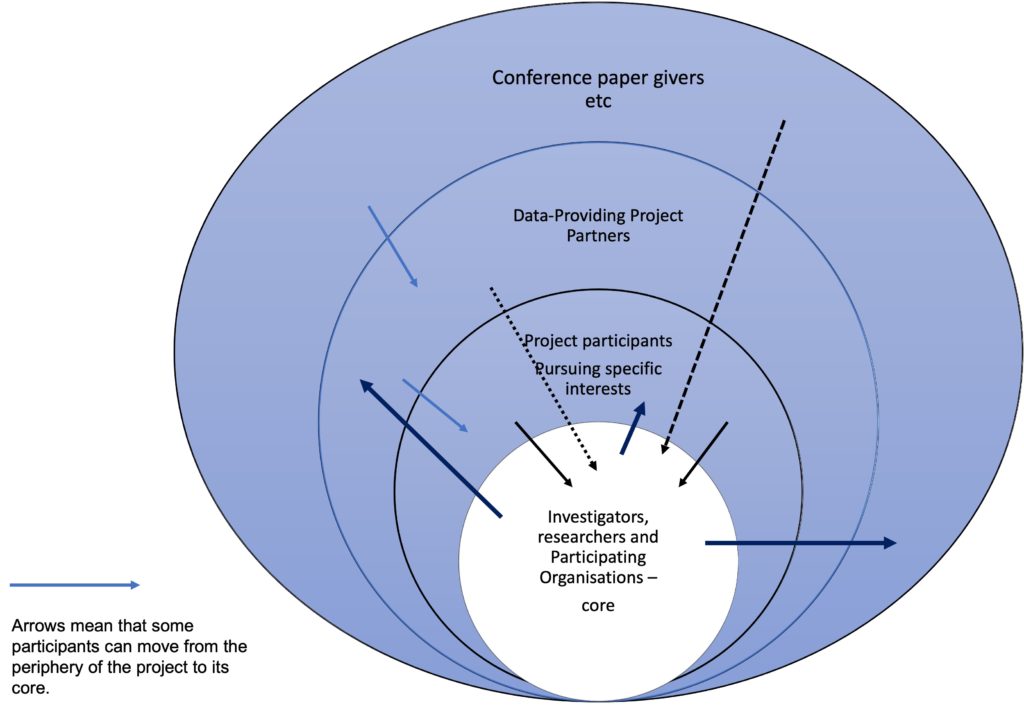

If we mean by ‘The Congruence Engine’ the sum of an investigation by people, rather than the construction of a device or a program, to create congruence, who are the ‘we’ who constitute the ‘engine’?

The core project team will invite a wide range of people interested in industrial history to witness and selectively to join in with our investigation. The project includes a focus on three industrial sectors in turn – textiles, energy and communications. The idea is that the choice of subject areas can, between them, cover the whole of the industrial period, but also retain living relevance, whether that be to do with the legacies of empire (textiles), climate change (energy), or the cultural and social revolutions wrought by new media (communications).

For each subject area, historians, curators and researchers are already employed in the project, and more will be invited to join as the project develops. Another 15 organisations have already said that they are happy to provide data to the project about their collections. In practice, as the project rolls through its differing phases, which datasets – big and small – we use will be determined by the needs of the several mini-investigations under way at any one time. The representatives of the museums, archives, galleries, societies and other organisations may well choose to become involved in some of these investigations. They will bring their data with them as they take part in the investigation for the sake of the insights they will gain into the benefits of applying the project’s digital techniques to their own collections and practice. It may be, for example, that an exhibition may be curated using the techniques we will trial, or that they will be able to enhance the cataloguing of a collection in their care by comparison with the resources of other institutions.

It may also be that the Congruence Engine team will ask organisations to devote effort to the core of the project; in this way we can expect collections, organisations and people to move between more and less active roles in association with, and within, the Congruence Engine.