Written by Jon Agar, with contributions from Tim Boon, Bernard Musesengwe, Stefania Zardini Lacedelli, Daniel Belteki and Graeme Gooday.

In May 2023 a party of Congruence Engine collaborators visited the National Collection Centre in Wiltshire, home to an increasing amount of the Science Museum Group Collection. The Congruence Engine is all about using digital methods to make new links between collections of industrial heritage. But sometimes we can get a bit lost in code. Here was a chance to remind ourselves of the diversity of material things and the challenges of interpretation. Our encounters sparked ambitious visions of how collections could be digitally reassembled to enable new stories of the past, present and future.

The scale of the National Collections Centre (NCC) became immediately evident as soon as our minibus arrived. The old hangars of this wartime airfield are big enough to contain jet aircraft (and they do). I’d seen these colossal structures on my last visit a few years ago, when the great decanting of the Science Museum Group’s smaller objects from Blythe House had just begun. Now there is a new, very large collection management facility, which has begun to welcome the Group’s curators and will open for public tours, school and research visits next year.

The tour of the building was guided by three NCC Collections Access Facilitators. Helen, Mark and Robyn had been asked to select a few objects that they thought might speak to the three Congruence Engine strands of Energy, Textiles and Communications.

Robyn showed us lots of mining lamps, a 16th-century wooden mining shovel and models of mining shafts. Helen showed us a neolithic heckling comb, Richard Arkwright’s distaff and a punched card maker for Jacquard looms. Mark chose a 1923 copy of Thomas Edison’s apparatus for recording sound (made when Edison asked for the original back), a recording phonograph, and a Fairlight CMI, which was one of the first sound samplers on the market.

We stopped by the Photography studio, a big dark-curtained room of tables and gantries where Andy, Jamie and Josh were capturing images of objects in the collection.

Then we were set loose with a brief to find an object that spoke to us, and be ready to share the stories we might tell. I was soon feeling lost in the maze.

The building has a quite overwhelming scale. Tall stacks of shelving recede from view. Each shelf holds objects with a tag and barcode that links each object to its record. The objects are organised within subject collections; although related objects may not be adjacent, which makes them difficult to understand, they can all be located via this new barcode system. Put simply, a visitor is faced with a multitude of objects, each of which may or may not be recognizable in general terms – a telephone, a piece of chemical apparatus, a spinning wheel – but whose specific identity and provenance is unreadable at a glance.

Later we gathered together and reflected on what we had seen. Tim Boon, Congruence Engine PI and someone who knows the National Collections Centre well, reported that he arrives at the site with a mixture of excitement – a ‘promised land’ of historical artefacts – and depression: a dispiriting feeling of facing tens of thousands of mute objects whose stories are not known and may never be known.

Yet this is where Congruence Engine can help.

Visions of reassembly

In what ways might digital tools allow the reassembly of the collections – not only at the National Collections Centre but also perhaps at partner museums and archives – in ways that assist historical interpretation? In my mind such reassembly could be broad or focused.

In the broadest vision, imagine if all objects could be digitally rearranged, bringing objects closer if they share characteristics across dimensions such as technological type, location of manufacture or use, association with individuals, and so on. A great virtual, flexibly reorderable library of artefacts. What significant patterns of connection would emerge? What gaps revealed? Daniel Belteki also shares this vision: can we ‘imagine walking into stores of multiple museums at once? And what would that experience look like? Could we ‘develop a tool that allows for mapping the existing arrangement of the store, with the added feature of the tool offering suggestions for the arrangements based on the combination of curatorial vision, historical connections, and practical considerations’?

In the focused vision, objects might be rearranged to prompt particular narratives. As Stefania Zardini asked: how can we construct journeys that stop at objects along the way? How might these stories reach new audiences via websites or other media?

These thoughts struck many of us, and we wondered why. Belteki again: ‘what might have prompted us to start thinking about reassembling the collections. Was it simply due to all of us working on the same project? Or was it something more material? Perhaps being confronted with a seemingly random arrangement of items prompted us to arrange them in ways that make sense to us. If that was the case, then how can we implement such prompting of the “assembling imagination” into the digital tools that we are developing?’

Remember that the hard work has been largely completed: each object is locatable, digitally readable, and linked to catalogue data and metadata. The required next steps are digital tools to rearrange and reconnect.

To my mind, such a step would also be necessary, perhaps existential, for the success of the National Collections Centre project as a whole. It seems to me that the NCC is too remote for direct inspection of objects ever to be a significant mode of access for many researchers. But Congruence Engine digital techniques could make collections more legible to researchers and enable pre-visit preparations for the people who do come, and that will maximise the benefit of engaging with the objects. The heritage is too rich and has too much potential not to be made available for reflection and research.

What is in the collection?

In one sense what we saw at the National Collections Centre was the outcome of an institution established in the late nineteenth-century that has collected the debris of waves of deindustrialization and obsolescence in the twentieth century. Yet the process was also more active than this image suggests. As Graeme Gooday remarked, the presence of every object was a result of a human being deciding not to throw it away. (One might speculate what an “anti-museum” filled only with things that had been chosen for disposal would look like.) Helen suggested that donation of objects to institutions like the Science Museum might provide, in an odd way, a little piece of immortality.

Immortality is a meagre reward if no-one commemorates the departed. Commemoration is remembering – telling stories that have meaning to a community – together.

Congruence Engine aims to create tools that would facilitate the telling of historical stories at a scale commensurate with the size of the collection. On an individual level we wanted to see what such narratives might be like. So we each selected an object that we had seen and shared what stories we could tell.

The results were as diverse as the group:

- a dictograph for internal office communication (Tim Boon, also see below);

- a miner’s pickaxe that not only had family resonances but was also a tool of a shape with a pedigree of millennia (Simon Popple);

- an ADSL cable, now obsolete but a symbol of connection (Jamie Unwin);

- a saddle maker’s hand tool, perhaps part of a set that could be reassembled virtually (Tim Procter);

- a Philips video cassette recorder from 1975, a relic of the format wars but also a reminder of the culture of home recording (Geoff Belknap);

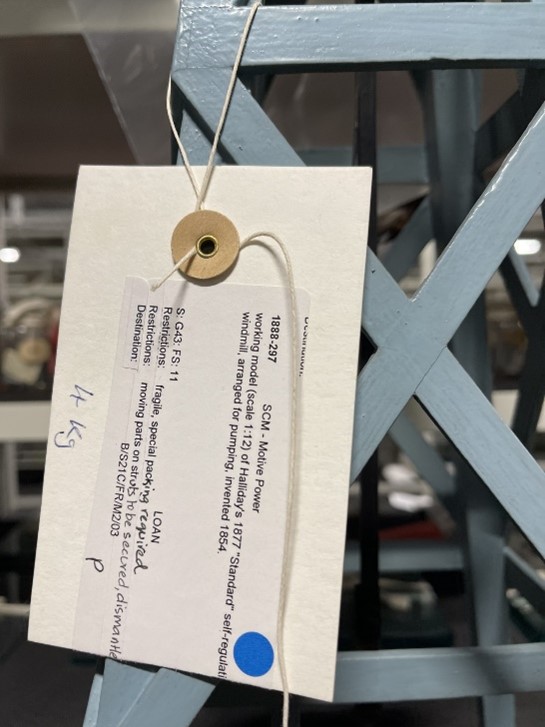

- a working model of an 1870s windmill (Graeme Gooday, see below);

- a shuttle (chosen by Stefania Zardini in an experimental test of whether specific objects could be searched for and found, see below);

- a model of a strand-making machine of a kind seen at Quarry Bank Mill (Arran Rees);

- a model of a cooling tower (Daniel Belteki, who is using digital techniques to map and interpret the distribution of power stations)

- an acetylene lamp, similar to one found in Newcastle’s Discovery museum (Bernard Musesengwe, see below)

- a model of the microwave radio station at Purdown, Bristol (Jon Agar)

- a Neolithic loom weight (Pamela Keeton).

Some patterns can be seen amongst our choices. Tim Boon noticed, first, the links to personal or family experiences; second, the curiosity evidenced by the ‘what is that?’ reaction we all reported; third, the explicit and potential connections people had made with objects in other collections; and, finally, the steps towards interpretation we were already able to make or could envisage. I would also call attention to the proportion of models in our selections, higher than the proportion of models in the collection overall. Perhaps this bias was due to the attractions of the miniature. But perhaps, too, it reflects the fact that the technological systems that give shape to our world cannot be collected whole.

As individuals each of us could choose an object, usually, to be honest, one of a type that we knew something about already, and could spin a tale around it. With a day or two of study time we could fill these stories out and place them on robust evidential foundations. We might even feel we could, over a month or so, write a paper for the Science Museum Journal. But this sort of handstitched, individual-scale scholarship – individual objects and individual researchers – would leave the vast bulk of the objects in the National Collections Centre untouched and unstudied, even if hundreds of us researched for a hundred years. We need techniques that work at scale. Time to learn more lessons from the Jacquard loom.

Tim’s object: Dictograph Office Intercom (1970-259)

(Tim Boon is Science Museum Group Head of Research and Public History, and Principal Investigator of Congruence Engine)

Nick Thomas lists the encountering of collection items in the store as one of his three ‘defining moments’ of museum-style research, ‘museum as method’ (the others are juxtaposition of different objects together and the labelling of things (Thomas 2010)). And so it was on our visit to NCC on 23rd May. Amidst the familiar, the banal and the incomprehensible objects on the shelves, a few leapt out to the eye of this curator; let me take just one example:

This is an office intercom with eleven lines. This posed for me a question about the interaction of technological development with commercial practice. For there to be a market for such devices, businesses must have been persuaded that speech between different parts of the organisation was valuable for the conduct of business; it implies distributed offices rather than our own nearly ubiquitous open-plan fashion. And it implies that the business in question favoured immediacy of communication (as opposed, for example, writing a memo and waiting for a messenger to carry it to another office to gain a response). In other words, this object suggests itself to me as the previous inhabitant of a techno-business ‘ecological’ niche. I may be entirely wrong, but the object by virtue of its design, probably, has provoked in my mind a set of research questions that I could pursue. This is typical of museum-style research that starts from the object and moves out to the context.

Thomas, Nicholas, ‘The Museum as Method’, Museum Anthropology, 33.1 (2010), 6–10 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01070.x>

Bernard’s object: acetylene lamp

(Bernard Musesengwe, Assistant Keeper of History, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums)

The Impact of Acetylene Lamps on Night Time Travel: Enhancing Safety and Extending Journeys

The introduction of acetylene lamps revolutionised night time travel for bicycles and cars, significantly improving safety and efficiency. These lamps provided a bright and reliable light source and incorporated signalling features, enhancing visibility on the road and enabling longer journeys. This contribution explores the challenges and limitations associated with acetylene lamps, their significance in lighting systems and material culture, and acknowledges their role in paving the way for modern lighting systems.

Challenges and Limitations: Despite their advancements, acetylene lamps posed several challenges. Regular maintenance, including checks and adjustments, was essential to ensure proper functionality. Users also needed to periodically refill the lamps with acetylene gas, which proved inconvenient. Safety concerns arose due to the highly flammable nature of acetylene gas, demanding careful handling. Additionally, the lamps faced issues during cold weather when the water inside would freeze, interrupting the gas generation process. However, an innovative solution emerged—mixing alcohol with the water lowered its freezing point, enabling more reliable operation in cold conditions. This ingenious adaptation demonstrated early users’ resourcefulness in overcoming the limitations of the technology.

Lighting Systems and Material Culture: Acetylene lamps not only had practical applications but also offer insights into past lighting systems and material culture. They marked a transition from traditional lighting methods to more efficient energy systems. The use of acetylene gas and advancements in lamp design reflected the evolving material culture and aesthetic preferences of their time. Furthermore, these lamps exemplified the impact of industrialisation on the mass production of lighting devices. Their introduction influenced the development of subsequent lighting technologies, contributing to the advancements seen in modern lighting systems today.

Conclusion: The introduction of acetylene lamps had a profound impact on night time travel, improving safety and extending the possibilities of transportation during dark hours. Recognising and understanding the challenges and innovations of the past allows us to appreciate the remarkable progress made in vehicular illumination. Acetylene lamps played a vital role in illuminating the path for early motorists and cyclists. As we enjoy the convenience and safety of modern lighting systems, let us remember the lamps that paved the way for brighter and safer journeys.

Illuminating Engineering Society. (1956). “Automotive Lighting 1906-1956”, Illuminating Engineering, 51 (1), pp. 128-132.

Moore, D.W. (1998). Headlamp History and Harmonisation. The University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute Report.

Tenz, J. (2016). The history of car lighting – carbide ca. 1907. https://www.carlightblog.com/2016/08/01/the-history-of-car-lighting-carbide-ca-1907/

Graeme’s object: a self-regulating windmill

(Graeme Gooday is Professor of History of Science and Technology, Co-Investigator on the AHRC-funded Congruence Engine project)

The ancient technology of windmills has been in use for four millennia in China to pump water, and for over a thousand years ago in Persia for grinding cereals. Why, then, would the Science Museum/National Collection Centre store hold a scale model of a new form from the mid-19th century? Obviously as a working miniature it had an educational/demonstration function: its novel feature was a ‘governor’ which ensured that the plane of blade rotation adjusted automatically to any change of wind direction. This was not just a gigantic weather-vane. Daniel Halliday of Connecticut, USA, patented this governor in 1854 as a mechanism to enable windmills across rural USA to pump water continuously and efficiently, without need for manual resetting and with less risk of destruction in violent weather.

This scenario speaks to the wider use of wind power across the USA until eclipsed by the apparent economic benefits of fossil fuels in the 1950s; tellingly this was just 20 years before the oil crisis of the mid-1970s returned energy strategists to approach wind turbines as a more sustainable future energy source. So what? From this perspective, wind power has actually only had the briefest of interregnums in millennia of significance; and given our current Anthropogenic climate crisis, its significance looks set to grow and continue indefinitely. By contrast the past 150 years of petroleum driven economies and conflicts destined to be a fleeting harmful episode that we cannot relegate too swiftly to obsolescence in museum stores!

In terms of the Congruence Engine priorities, what useful inter-collection connections can be made to speak to this longue durée history of wind power? One obvious linkage is to the Science Museum’s records of recent innovations in sustainable energy such as the UK’s largest wind turbine, the LS1 Prototype operated on Orkney, 1988-1997. More generally there is a broad turbine history in the (never-outmoded) technology of water power. The Science and Society library on ‘Wind and Water power pre-1900’ already connects the Halliday device to a 1:6 scale working model of a water vortex turbine that had been patented by James Thomson (Lord Kelvin’s brother) in Belfast in 1850. This is one of numerous 19th century water power vortex turbines evidenced in Science Museum collections e.g. the Fourneyron of 1837. An 1877 fragment of a Thomson vortex turbine from Kendall (Lake District) is also held by the Science Museum, a version of which was later installed in the UK’s first hydroelectric plant at Cragside in Northumberland c,1885.

Overall the collections of vortex turbines used in windmills and hydro-power sets a key context for the widely used high-efficient Parsons steam turbine (1884), so well represented in Science Museum collections, but for patent-related originality claims not explicitly connected to any precursor vortex turbine technologies. By digitally linking these diverse devices we could thus create an alternative narrative of continuity in sustainable energy technology which contextualises Parsons’ famous innovation within a long ancestry of devices designed to generate energy without recourse to fossil fuels.

Stefania’s object: weaving shuttle

(Stefania Zardini Lacedelli is a Research Fellow on the Congruence Engine project)

The weaving shuttle and the steady tune

During our visit at the National Collection Centre, my attention was drawn towards a shelf of weaving shuttles, a key component of the textile machinery mentioned in the collection of folk songs from Lancashire I am annotating with Jennifer Reid. The shuttle appears several times in the anthology, and opens the first lines of ‘The Weaver’s song’, a song by John Clegg adapted by Harry Boardman:

Clatterin’ loom an’ whirlin’ wheel, Flyin shuttle an’ steady reel

This is wark to make a mon feel There’s wur jobs nor weighvin’ I’ time o’ need’

Invented by John Kay in 1733 to assist in the quick back and forth motion of the loom, the flying shuttle paved the way for the transition from handlooms to power looms. The item description on the online collection website clarifies that this is a power loom shuttle which encapsulates a further technological improvement: ‘the spring tongue’ – the description states ‘is hinged like a pocket-knife, so that it projects out from the mortise when inserting a fresh cop of yarn (…) allowing a cop of greater length to be used’. While reading this, I realized how the object which was standing in front of me was highly representative of this song, as its underlying rhythm recalls the faster motion of the power loom and all the implications this technology had on the life of the textile workers.