The trepidation of a fourteen-year-old boy on his first day of work at the coal mine. The excitement of three Italian sisters who had left their home to work in a Yorkshire mill, when they reunited for the first time. A fight between an old miners’ lift cage and a new one, representing the impact of a technological innovation on the lives of miners. The steady tune of the textile machines played from light until dark, expressing the incessant rhythm of the work in the mill. This knowledge is not in written documents, but in the life experience of entire generations of miners and mill workers, who told their stories in a sonic form.

Derek Ward interviewed by Colin Hyde. Audio extract from Mines of Memory, East Midlands Oral History Archive.

Oral Histories and folk songs have been, in Congruence Engine, not only a type of historical material that we can connect to collections to expand the meaning of objects, but a whole new horizon of possibilities to conceive our relationship with the past. An audio recording of a miner talking about his everyday work underground, or a song expressing the anger of mill workers who lost their jobs due to increasing automation, immediately connect us with the human and emotional dimensions of industrial history. These recordings can bring out the wealth of life experiences, emotions and feelings which relate to museum objects. It is no coincidence that songs and spoken words are often used in museums in the context of exhibition or in-gallery narratives to bring collections to life.

And yet such profoundly human material, which can give voice to generations of industrial workers and can reveal stories of migrations, human effort and endurance, is not easily accessible. Part of this knowledge is still captured only in analogue form and, when it is digitized, it is often dispersed and distributed across different collections. And most importantly, a fundamental part of this knowledge still lives in the mind, heart and spirit of expert folk communities, which continue to sing these stories and experiences, keeping this heritage alive.

Music video of “The Row Between the Cages” from the Mining Review Year 11 No.1.

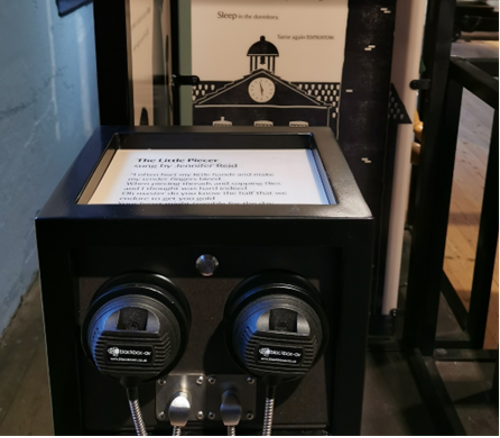

This is why we developed an investigation to explore how we can use machine learning and Artificial Intelligence to connect this sonic material with museum collections and other historical sources, as well as with the living, embodied and experiential knowledge of folk son’ experts. To guide us in the discovery of this material was Jennifer Reid, a ‘singing historian’, as she describes her job and mission. She helped us to annotate a corpus of mining and textile folk songs, challenging us to go beyond the words in the lyrics and surface the knowledge and expertise of the textile and mining workers: their troubles, their desires, their suffering, their imagination. We used an annotation tool called Label Studio to capture her insights and learn by this knowledge, and we are creating a digital pipeline that will enable us to connect songs with objects, technical expertise with machines, collections with stories, material culture with sound culture.

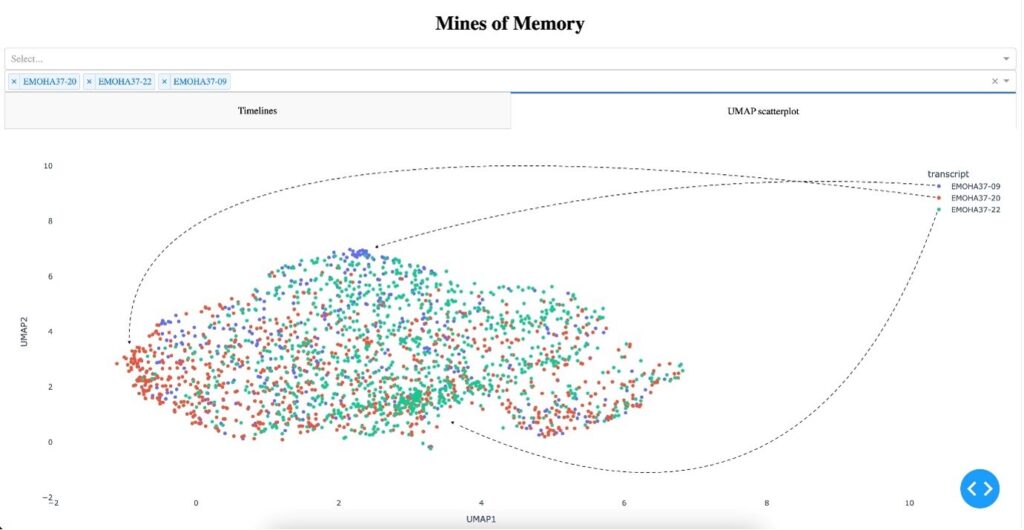

In parallel, we are looking at the latest advancements in Automatic Speech Recognition and Natural Language Processing to expand the discoverability of another type of sound heritage: Oral History. Thanks to audio recording technology, the life experiences of industrial workers have been collected over the past century by passionate oral historians, so expanding the social history of the Industrial Revolution. But also in this case, even when this material is digitized, it is not easily searchable and accessible. In collaboration with the Institute for Digital Culture of the University of Leicester, we are designing a visualization tool that will allow us to interact with this audio material in entirely new ways, searching across a web of automatically generated topics and finding similarities, patterns and unexpected connections across different interviews.

The potential applications of this work are huge. The processes we discovered can change not only the way curators and historians work, but also transform the way we research the past and interact with different types of memories. Artificial intelligence can help us to surface connections which are not immediately visible, give voice to stories which are not often told, and highlight the value of forms of knowledge which have been less represented in cultural and historical research. Museums, born as physical institutions aimed at preserving and displaying material culture, are increasingly interacting with intangible, digitized, collaborative, networked forms of heritage, becoming distributed, participatory and interconnected themselves. Sound is a powerful medium to show how material and intangible culture are inextricably connected, that – without memories, stories, and life experiences – all the objects and documents collected by cultural institutions risk remaining silent.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my co-investigators Daniel Belteki, Stef De Sabbata and Jennifer Reid, without whom this work would not have been possible. My deepest thanks also to all the members of Congruence Engine network who contributed to the Oral History and Folk Songs investigations: in particular: Kaspar Beelen, Alex Butterworth, Paul Craddock, Sally Horrocks, Colin Hyde, Kunika Kono, Cal Murphy Barton, Felix Needham-Simpson, Simon Popple, Tim Smith.