After three years as Principal Investigator of the Congruence Engine project, I found myself giving a plenary presentation to the ‘Towards a National Collection’ end of programme conference. Our project was one of five ‘Discovery Projects’ all targeted at the problem of making collections in our country accessible to everyone via their digital records.

Shoehorning such a rich, diverse and, well, interesting project as Congruence Engine into 25 minutes felt daunting until I hit on the idea of framing it as an argument about what we did, why, and with what conclusions.

I started with the argument in compressed form …

We want to make all UK heritage collections fully accessible together, not just institution-by institution as now, to those who would use them. The means to achieve this are their digital records. But, because of the history of heritage organisations, our current records are ill-suited for this purpose: in the main, they are thin, inconsistent and isolate collections items from the contexts in which they make sense. In Congruence Engine, we have therefore experimentally created ways to link collections with historical data as well as with each other, techniques that in various ways overcome these weaknesses. Because the creation of useful collections linkage requires the agency of its potential users, and because computing techniques are fallible, UK collections linkage requires a social machine for the task: a human-technical approach that mobilises human motivation and thereby overcomes machine incapacities. Many of our techniques employ machine learning, with the result that we have within our grasp the capacity to overcome decades of limited investment in collection documentation. But, because we are using these techniques, we confront a series of ethical issues that demand to be researched, even as we press for the resources to create user interfaces and scalable prototypes for a future infrastructure, which together can reveal the potential of what we have glimpsed.

…and then I took it apart, phrase-by-phrase to open-up our thinking:

Our Purpose

Congruence Engine took the TaNC mandate and researched at the proof-of-concept level a wide variety of techniques that could be applied to make all UK heritage collections fully accessible together, not just institution-by institution as now, to those who would use them. The project has proceeded on the basis that to do good historical and curatorial work, it would be insufficient to simply connect museums to museums, or just archives to archives, for example. UK collections linkage worth having should work intermedially across repositories that hold: objects, documents, pictures, records of historic places and sound and moving image media relevant to any subject. In Congruence Engine that subject is industrial history, but what we have done will be relevant for any subject and any collection type.

Our ultimate target for Congruence Engine is that the techniques we have developed will be deployed to bring more people to the collections themselves, each visitor empowered to integrate collections into their historical pursuits. We are concerned that the term ‘UK digital collection’ that has, for the TaNC Directorate, replaced the previous term ‘national collection’ is also not quite right. Evidently ‘national’ risks being read as implying an (unintended) exceptionalism, even a chauvinistic nationalism. But it also implies an unsustainable limitation for industrial collections that have international histories. Our quarrel here is more with the suggestion of a national digital collection separate from its referents, the collections. It is important to us as heritage sector people that the collections-centred digital resource for history that we are proposing is not an alternative to contact with the material – real objects, places, pictures and documents, and the experiences created in the encounter with them. Rather, we are creating an invitation and a means for people to experience tangible and intangible heritage directly: to encourage visits to heritage collections on the basis of what they contain: to the stores and archives, museums, libraries, galleries, theatres and cinemas, even as we promote the new kinds of digitally enabled histories and curatorial practice that will use them.

From the grant application onwards, we have been clear that the core direct audience for Congruence Engine would be people interested in industrial history, in whatever way. We have been mainly concerned with amateur and professional historians and curators or archivists. But potential users of collections often do not know of the existence of collections relevant to their interests, or else they know they exist but cannot gain access to them.

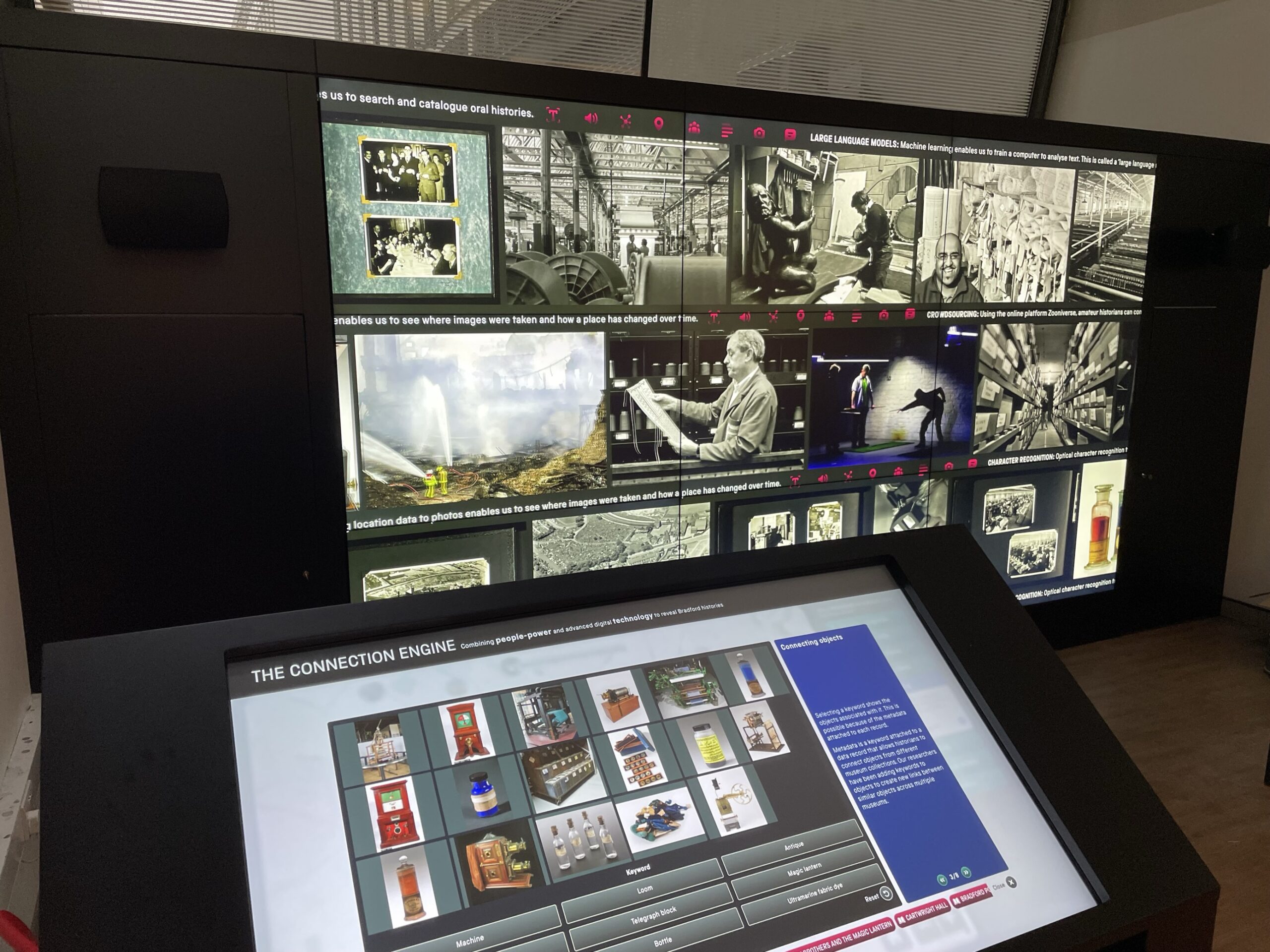

Further down the line, the improvements we propose will benefit wider groups of people, including casual visitors to museums. Congruence Engine’s end-of-project digital exhibit models this by addressing the visiting audience at the Science and Media Museum in Bradford. Here again we think that active amateur historians will be particularly interested, but we are also addressing people from West Yorkshire who will be attracted to explore the linked histories of where they live, as well as anyone excited to see how digital work can reveal collections and history. The principle is eminently extensible to other towns, regions and, indeed to the nation and beyond.

The means to achieve this ambition to make all UK heritage collections fully accessible together are their digital records. But, because of the history of heritage organisations, our current records are ill-suited for this purpose. Only catalogue records have the potential to make collections available to these users because virtually every heritage organisation has too large a collection to display everything, so much is in store. In the case of the Science Museum, for example, a positive decision was made seven decades ago to create a reserve collection. At present, that ‘reserve’ amounts to some 97% of the total collection. But, because of the history of heritage organisations, our current digital records are ill suited for this purpose of truly making collections available: in the main, they are thin, inconsistent and isolate collections items from the contexts in which they make sense.

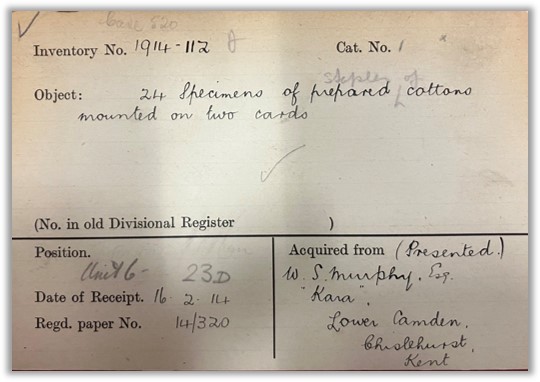

- Many of our records are derived from audit records and so they are thin, by which we mean that their brevity often means that the descriptions lack significant details, such as purposes, associated names, places or accurate dates.

- Objects may be inconsistently recorded within a collection, perhaps because the curator lacks time to bring old records up to quality with those for new acquisitions. But the greater inconsistency is between different kinds of collections. Museums are different from archives and use different data standards. As we know, libraries gained a huge amount by the adoption of the MARC standard, itself the product of the application of computers, from 1965 onwards. Whilst museums use the Spectrum collections management standard for documentation processes, effectively there has been no universally adopted cataloguing or data standard. And because of heritage organisations’ differing historical purposes, what has mattered to each of them – and therefore what is recorded in their data – may well have differed from organisation to organisation. And because of heritage organisations’ differing historical purposes, what has mattered to each of them – and therefore what is encoded in their data – has differed from organisation to organisation.

- But, from the interpretive point of view, the major weakness of data representing heritage items is that it isolates collections items from the contexts in which they make sense.

In museums, data represents single items rather than the collections in which they make relational sense to their curators, a loom in a textile machinery collection, for example.

But, more than that, the very act of collecting removes an item from its social historical ecology, and puts it to work otherwise. Our loom, for example, ceased to be the working tool of individual weavers and became the representative of a stage in the historical development of weaving equipment.

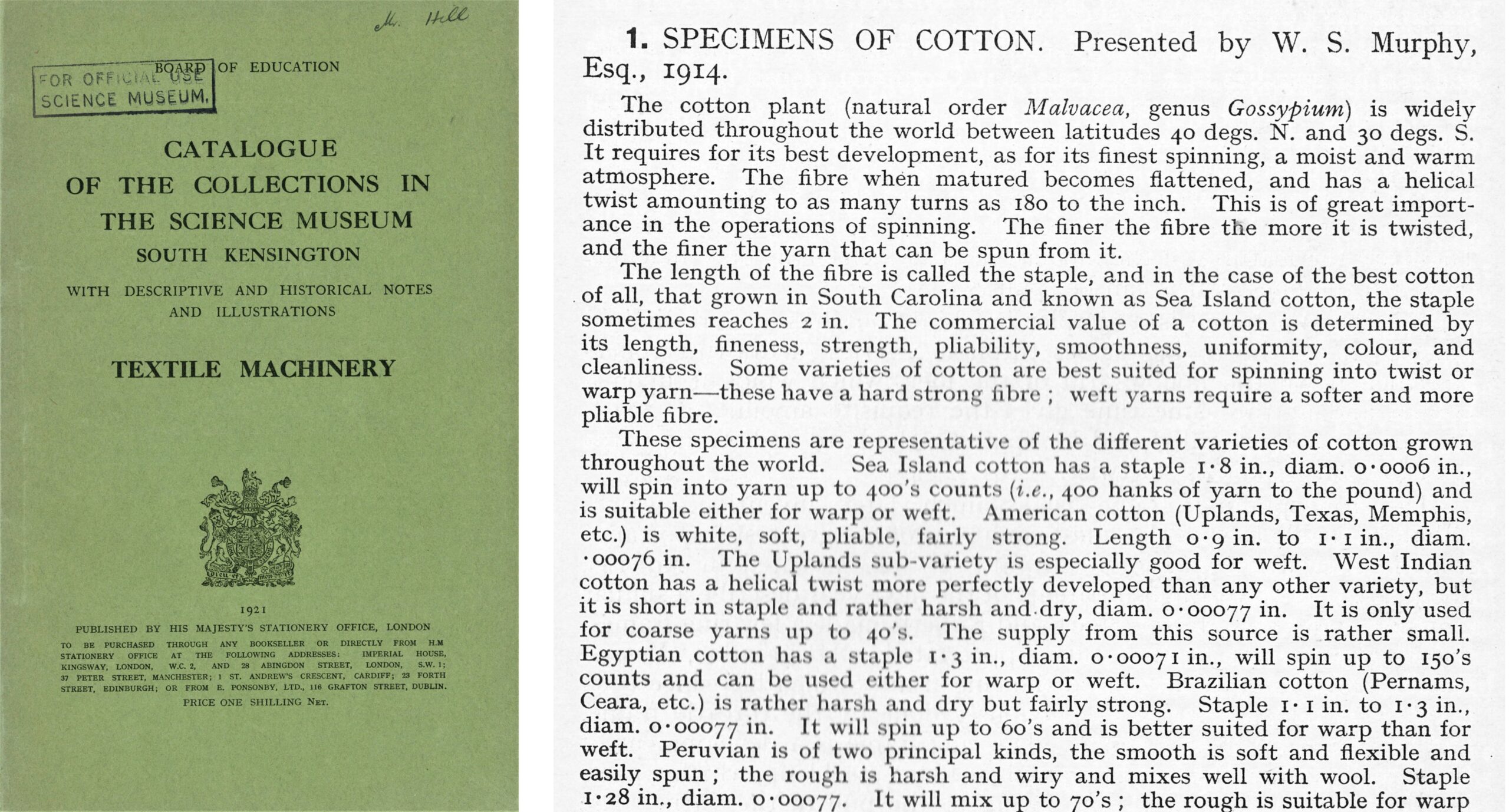

Heritage organisations have records of items in their collections for two reasons: for audit and for access and interpretation. As for audit, these organisations need to know what they have, what its legal status is, and where it can be found. At the Science Museum, over decades collections were audited using record cards that carried minimal identifying information, good enough to distinguish one item from another, but little more. A century ago, the Museum separately had records for interpretive purposes: curators wrote definitive display labels for objects and, in the majority of cases, these were gathered together in printed catalogues with some interpretive introductory text.

But when it ‘computerised’ its catalogue, the Science Museum – which is not unusual among its peers in this respect – used its audit records, not its catalogues. This is the original reason for the thin data that represents our objects online. Moving cataloguing information up the scale to full enhanced record status is an aim we constantly seek to address. But the funding to support this has always been difficult to find because museums and galleries properly favour expenditure on the displays seen by millions of visitors over the backroom work of cataloguing. This state of affairs has inevitably been reinforced over the last 40 years as UK museums and galleries have increasingly adopted the practices of commercial businesses, investing in the quality of the ‘product’ (the displays) not least as a response to reduced governmental funding. And it’s worth stating that this problem of slight data is often much worse for the small museums that have even less money than the nationals. These heritage organisations may only hold audit level records, and their databases may only be for internal collections management purposes.

Congruence Engine linkage techniques

In summary, the records we work with make it difficult for researchers to see these collections and to use the items within them as normal recourses for their investigations. That is especially true of object and media collections. The styles of digital historical work that use data most successfully are those where data has been made palatable to users, for example the vast historical newspaper corpora of the British Library. Another example would be family historians’ use of census data via Ancestry and Find My Past. These latter commercial services first digitally reproduce analogue access to demographic data sources, then template specific practices around genealogy in such a way that has not happened with most other kinds of mass data: trade directories, for example, may have been digitised (notably Leicester University Library’s collection), but they have not been datafied. And in neither case – the census or the directories – is the data yet widely or freely available in a form that makes it fully interoperable and free to use as public data should be.

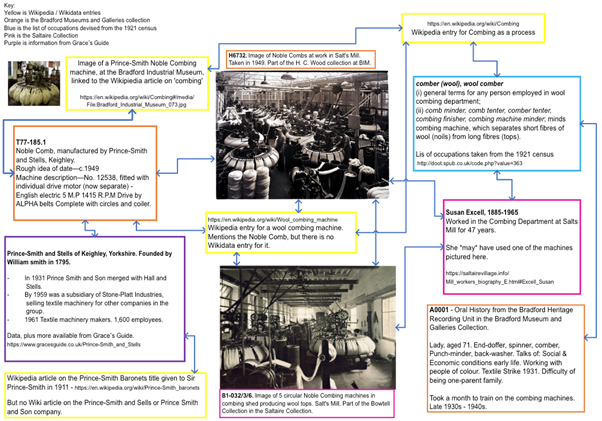

In Congruence Engine, we therefore experimentally created ways to link collections and historical data. Most of our investigations were experiments as if we lived in a world of linkable open data: we have converted collections datasets from our 15 partners so that they can become linkable data, and we have created datasets that enable collections of objects to speak to each other. I am referring here to what we called ‘connective tissue data’. To explain: It became clear to us that to make collections of all kinds linkable to each other required the ontological leap of counting the data within collections as part of the UK collection, be it currently analogue or digital. Along with Census data, trade directories were one of the inciting categories: because they list individuals, addresses, trades and businesses, they hold the data that can, potentially, associate people, work, machines, products, places and the rest. Historical individuals designated their occupations themselves for these directories and the Census; and this is especially powerful for linkage: To take one example from the project’s research, Susan Excell, a wool comber living in Saltaire from around 1900, can be expected to have used a ‘Noble Comb’, a particular kind of machine, locatable to a particular floor in Salt’s Mill, preserved in the Bradford Industrial Museum, and shown in historical photographs. To be able to make those links at an individual level would be satisfying for a family historian. But potentially this can be done at the level of huge data: a dense filigree of connection incorporating millions of people and heritage collection items that could enable a subtle and detailed social history of people, work and machines.

In 2022-3, in what may be seen retrospectively as the second in four major phases – or ‘eras’ – of the project, as we sought to make it more intrinsically digital, we increasingly replaced our initial language of assemblage and association of heritage collections with one specifically of their linkage, of linked (open) data. Our aim at this stage was to go beyond the scale of normal, case-study-based, historical work like the Susan Excell example, to enable finely textured research at the level of factory workforces, towns or regions. This required a return to the approach of our previous project under the TaNC funding, Heritage Connector, in that we were once again gathering datasets, extracting terms and using graph databases. Our aim has been that digital linkage of items across collections and with historical data would enable individual items to be reunited with their constituting contexts, returning the ‘orphan object’ back to the ‘family’ of its historical origins. And so, most of the project investigations explored differing ways of achieving linkage. Some of these are ‘live’ in that they exist ‘in the wild’ in online data and in museum collections management systems. An example here is the Wikidata taxonomy for textile machinery we have created. Others have been achieved by combination within temporary housing in graph databases of derivatives from datasets lent by our project partners. For example, starting with various unstructured sources relevant to industrial Bradford – including lists of historic mills, Census and directory-derived data – we have been working to develop methods to extract graphs of entities (such as people, machines, trades and places) and their relationships. We have been bringing these together in an expanding knowledge graph implemented in a Neo4j graph database. The idea is that this could serve as a sandpit for human validation, regularisation and then further linkage using additional data science methods.

In the context of Congruence Engine as a project devoted to proof-of-concept, we have been concerned to demonstrate multiple ways in which linkage could be effected. In terms of next steps, the techniques will be experimentally replicable via our GitHub pages, but only at this stage by individuals and organisations possessed of the appropriate skills. Their widespread adoption will require, alongside personal enthusiasm and motivation, policymaking and investment to be in place. These themes are being explored in the project’s second book, which lays out and reflects upon the potential decentralised methodology for creating the collections-linking digital resource for industrial history that we have sketched within the project.

Social Machine

Because the creation of a useful linked collection requires the agency of its potential users, and because computing techniques are fallible, the creation of UK collections linkage requires a social machine for the task: a human-technical approach that mobilises human motivation and thereby overcomes machine incapacities. Congruence Engine was, from the beginning, designed to be responsive to what potential users of a linked data resource would want to do with it. As we have argued, we want our investigations to make available collections and digital techniques to historians and curators to enable and enrich the kinds of history and curatorial work they are able to practice. In part this is to create a more responsive, more democratic, model of access to collections, driven from the periphery of need rather than from the (financially constrained) centre of provision. The national collection is so numerous as to be infinitely deep and wide, given that most archives are only enumerated, and digitised, to the part level, not yet the piece, let alone to the level of datafying each piece. Our expectation is that linkage will occur where people want to do it; it is impossible that every datapoint could be linked, but where a need is felt, then it can be. It is our task to enable this.

We say that part of the motivation is democratic, but the other is practical: most of the work needed for the creation of interoperable heritage data is human labour. We put on one side for the moment the troubling issue of tech companies’ use of cheap labour from the South to build their LLMs. There remains a benign aspect of human labour closer to home. The simpler digital tools such as Regular Expressions and OpenRefine can speed the regularisation of messy data, but their work must be intimately directed by humans. And then, the more computing-intensive work such as topic modelling or prompt engineering for interaction with large language models is necessarily human work, drawing on expert knowledge, or even simply on the human common sense not reproducible by artificial intelligence programs. These ‘intern’ and ‘cog’ style AI techniques are only tools, good at pattern-matching, but as useless without human interaction as a screwdriver without a hand.

So-called Generative AI ‘hallucinations’ – and we have seen plenty of those, not least when ChatGPT valuably converting a tabulated list of Bradford woollen mills to computer-readable form inserted some entirely fictitious examples – are not incidental wrinkles about to be ironed-out by clever programming. They are intrinsic products of the faux intelligence of these machines. Humans in the loop are required to remove them, just as pre-Ford, mechanics had to file-down machine parts so that they would work together.

Altogether, that is why we say that a social machine is required for the creation of UK collections linkage. We need the speed of automation, but we need the person’s occupancy of the human world to ensure its results make sense and are of value in that human world.

Machine Learning Techniques

We speak of overcoming decades of limited investment in cataloguing. I do need to state that, although at one level what we are proposing is a catch-up in documentation, in other ways the linked data solutions that we are proposing present an entirely new opportunity for realising the cultural capital of collections, which is effectively scarcely exploited at all. In addition to simpler computational techniques such as Regular Expressions or OpenRefine, we have also extensively used Large Language Model technologies. With ChatGPT being released at the end of our first year in November 2022, we were able – because the project’s action research methodology enabled this flexibility – to explore many possibilities that have arisen in the generative AI goldrush of the last two years.

On the side of text composition, the real power of text generative AI techniques is not at all in the automatic writing of closely argued historical scholarship, but in the vast speed-up in the creation of more functional prose for practical reasons. Investigations under the Congruence Engine umbrella have shown, for example, that, given a set of different commissioned researchers’ notes on previously uncatalogued files, ChatGPT can produce serviceable formatted catalogue descriptions. Or, again, film catalogue descriptions have been created from speech-to-text transcriptions of documentary film commentaries. If we are to standardise such digital pipelines, automation promises to enable more extensive cataloguing of collections, and therefore findability of collections items. The flat and uniformly formatted prose produced by generative AI programs is appropriate to such purposes in a way that would be purposeless in areas of interpretation that require human intention.

The project has employed both data scientists and humanities researchers. The way they have worked has shown the potential for the creation of hybrid individuals who have on the one hand curatorial and humanities instincts, and, on the other, a lived sense of what it means to work using data science techniques. For the techniques the Congruence Engine researchers have used, see our Final Report.

Ethics

Especially because we used Machine Learning / AI these techniques, we confront a series of ethical issues. As we have argued, many of the project’s successes from November 2022, after the release of readily usable Generative AI programs, relied on these techniques. In the experimental space of a research project, we felt an imperative to explore the affordances of these new LLM-based techniques. Our experience shows that we confront several different kinds of moral danger in this work, which together counsel caution. Especially worrying for our current geopolitical ethics is the way that the current and recent development of LLM technologies echoes the exploitative and extractive practices of the colonialism and imperialism with which we are elsewhere seeking to come to terms.

- We recognise that the training up until now of large language models on internet materials may well amount to a form of copyright theft.

- We also know that selection of texts and images for this purpose has been indiscriminate, so that archaic terms and now offensive attitudes may well be reproduced in the outputs of these models.

- We certainly know that the ‘stochastic parrot’ techniques on which these technologies operate do not have the discernment of a human reader and that close human supervision will continue to be a necessity. How can this be provided in a non-exploitative way, especially given that we know about the export of moderation and data work to the global south?

- We recognise that the environmental costs of running AI algorithms is high, in terms of water consumption, and especially of energy – to the extent that technology companies are buying-up the future outputs from whole wind farms, and are commissioning nuclear power stations. This development risks running roughshod over the climate emergency measures to which our organisations are committed.

- Many wise people are counselling that we are occupying just the latest in a series of AI ‘bubbles’, associated with hype about both the dangers and the capabilities of the current generation of technologies, each aimed to fuel what must be a time-limited gold rush. What happens in our applications when the bubble bursts?

- Implicated in all of this is a further area of ethical peril: as in blue collar occupations in the past, automation runs the risk of creating technological unemployment in the heritage sector. In Congruence Engine our ethos has been that these techniques could enable data-creation effort (read, ‘cataloguing’) that heritage organisations have rarely been able to afford. Ideally, mechanising this activity will eventually lead to displacement of curatorial work into more social roles related to using collections more creatively. But the record of historical precedent in relation to technological unemployment is mixed and transitions are often painful.

All this points to the need to develop well informed and critical ethics on a deliberative model (not just the issuing of guidelines) to guide the sector through the likely stormy next few years. With regard to the use of LLMs, it indicates the avoidance of trivial use, the investigation – and perhaps development of – open-source LLMs, and the championing of ‘minimal computing’ solutions. The sector will need to balance the costs of machine-learning solutions with the costs and benefits of choosing lower-tech, more labour-intensive, approaches.

As historians of science and technology we are conscious too that, reporting now at such a point of flux, we are also witnesses to a kind of technological change that we would at other times be analysing historically, and that the technical possibilities that we are able to articulate now will soon become part of the historical evidence for our period.

Next steps, as they seem to us

We can envisage a world of linked and open heritage data, in which not only is it easy to find related items across collections, but where any collections item – object, picture, archive document, film, historic building record – can be seen within a ‘data neighbourhood’, to use another of our project metaphors, a virtual reconstruction of the social-historical stratum from which it was removed at the point of acquisition. We can even imagine that world of linked and open data as covering all subject matter and all collections. But such a world is a distant prospect; as Alex Butterworth put it in our project manifesto:

Congruence Engine prototypes a framework for the creation of a national datascape of cultural heritage as an act of cathedral building: generational in its trajectory.

Before we can reach up to that vision, we will need to do more research to create tools and gain wisdom about ethical practice, in parallel with demonstrating the potential of collections linkage at scale by creating prototypes for future infrastructure:

- Tools and interfaces: a crucial area of research and development that we need. Most of the techniques we have developed have required convoluted pipelines and hand-coding using very new computing techniques that have been evolving fast. We need to equip the social machine of people who will link collections with apps and user interfaces so that everyday practitioners can readily create data from complex sources for their own purposes, and archive the resulting datasets in a sustainable manner.

- We need a programme of deliberative ethics with wide participation from organisations and individuals to work through the dangers and appetites for applying machine learning to heritage data.

- To move beyond proof-of-concept, we need to create scalable prototypes for future infrastructure: these will be diverse in subject, collections type and location. Amongst participants are likely to be: NMDC museums, IROs, local authority GLAMs, the Museum Data Service, suppliers of collections management systems and Wikimedia UK.

This text also appears as section nine of the project’s final report.

Conclusion for now

The project fulfilled its aim to provide proof of concept for what, in the end, we are calling ‘UK Collections Linkage’. The reports of the other four Discovery projects will also be found on the Zenodo repository. Together they provide very substantial evidence for what can be done now to work digitally with collections. On this evidence we can foresee a world of possibilities that certainly spell transformed levels of access to, and enjoyment of, the nation’s collections. AHRC have set a direction of travel in their policy recommendations from the programme. We can be optimistic that the cultural capital of our collections will be mobilised.